This is a true story. It’s 1943, and three Italians are planning to summit Mt Kenya. One’s a civil servant, one’s a doctor and one’s a sailor (this sounds like the set-up to a racist pub joke). Oh, and all three are prisoners at an Allies POW camp.

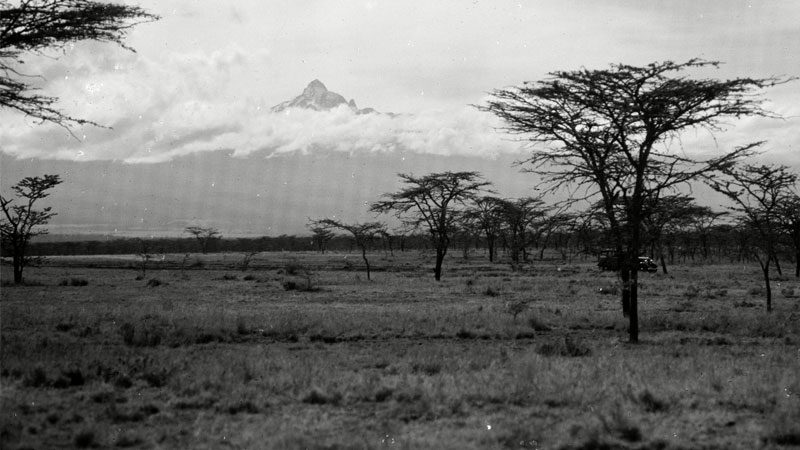

Felice Benuzzi (the civil servant) was a prisoner of the Allied camp at Nanyuki, at the foot of Mt Kenya from 1941, and spent two long years staring up at Africa’s second highest peak – before deciding to climb it. The three inmates made climbing gear out of barbed wire and plotted their route using a cartoon map they found on a tin of canned food. They escaped, fought their way past wild animals and, incredibly, reached the summit, spending 18 days on the slopes. Here’s the kicker: when they got back, so beautiful was the land they saw, and so rejuvenated was Benuzzi, that he snuck back into the camp resumed his life as a prisoner. They breed them conscientious in Italy.

A week might be a long time in politics, but the 72 years that have passed since Benuzzi made his climb are nothing to Africa’s mountains. Glaciers may come and go, but they tend to wax and wane on tectonic timescales, as unobservable in a human lifespan as the cooling of the sun or the gradual improvement of the Boston Red Socks. Or at least they used to.

In recent years climate change scientists have been studying the effects of global warming on several of Africa’s major glaciers, both on Mt Kenya and Kilimanjaro. And the results aren’t good.

On the northern ice fields on Kili, thought to be about 10,000 years old, 85 per cent of the ice volume disappeared between 1912 and 2011, and according to a 2012 report by NASA, by 2020 there will be no ice left on the mountain at all.

The glaciers on Mt Kenya tell a similar story. There you’ll find the Lewis, one of the most accurately and reliably mapped tropical glaciers in the world. Scientists have been studying its movements continuously since 1934, and in the last few decades have reported a disastrous recession (in a sort of quiet, scholarly way). In 1979, researchers mapped the Lewis and reported “drastic ice loss” in the four years since the previous study; in 1983 they discovered the same thing again. In 1995 they found “recession has accentuated in recent years”, and ten years after that “a drastic and progressive shrinkage”. In 2010 scientists claimed a further 23% loss since 2004 and (more worryingly) that the Lewis’ neighbouring glacier, the Gregory, “no longer exists”.

One of Intrepid Travel’s guides on Kilimanjaro, Samuel Kusamba, has experienced the mountain’s gradual decline firsthand. Samuel actually lives on the slopes of Kili, about 1,800m above sea level, and has been leading trekkers to the summit for the last 15 years.

“The view from the southern icefields and the Heim Glacier in particular is markedly different,” he says. “Glaciers that were once imposing landmarks exist now only as vertical ice flows.”

Samuel says the glaciers are a critical part of the mountain’s overall ecology. Without them, the region’s water sources are depleted and plant species are beginning to disappear. In countries like India and China (who produce the bulk of the world’s wheat and rice) melt water from Tibetan glaciers sustains rivers and crops during the dry season. Without them, a global food shortage isn’t out of the question.

None of these warnings are new, but they are timely. World Leaders are currently gathering at the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP21) in Paris to discuss the effects of global warming, and you can bet glaciers will be hot on the agenda. It’s the 11th time the parties have met since the ratification of the Kyoto Protocol in 1997, a depressing milestone when you consider that the World Bank found that (by 2006) energy-related carbon dioxide emissions had actually grown by 24%. Despite some government consensus that a) global warming exists and b) we’re causing it, the effects of the phenomenon have hardly been curbed at all.

One initiative that’s helping raise awareness of the glaciers’ plight is 25 Zero, a project set up by explorer and environmental scientist Tim Jarvis. There are only 25 mountains left with glaciers along the equator, and in 25 years scientists estimate those glaciers will be completely gone. Tim and other teams will be summiting five mountains on three continents during the 12 days of COP21 (including Kilimanjaro and Mt Kenya), advocating for clear and decisive action around greenhouse emissions during the conference. As part of the project, Intrepid will be leading the Kilimanjaro expedition to help raise awareness of the mountain’s dwindling ice fields.

Jarvis says 25zero is trying to put “a bit of friendly pressure on those attending Paris to say the world is watching. We really want a meaningful agreement to be reached.”

“Humans are very evidence-based creatures,” he says, “and I don’t mean evidence in terms of numbers and carefully argued positions, because then climate change would be an accepted reality.

What humans need to see is tangible evidence of change.”

What’s always been odd about climate change is how quickly it engenders a) antagonism or b) apathy. You’d think the literal destruction of the planet would be the least divisive issue in human history, but climate change scepticism (and often hostility) persists. Even after nearly a hundred years of conscientious and largely conclusive scientific study. People are described as ‘climate change believers’, which is reductive and dumb. You wouldn’t call someone who stands by Euclidian geometry a ‘maths believer’. It’s as if climate change reform is the equivalent of rallying support to buy Santa a better sleigh. A question of faith, not evidence.

Maybe it’s that we feel somehow complicit in the problem and, therefore, unwilling to face it. Are the world’s ice flows like our bank balance? We know there’s less there than we think, so it’s probably best not to check, keep spending big, and just hope it somehow all works out for the best? Unfortunately, it’s becoming more and more clear that, no only can we not afford that new iPhone 6s (metaphorically speaking) we’re nearing global overdraft. Burying our heads in the ice is, sadly, no longer an option.

Feature image c/o Marc, Flickr